Textus-Texts-Textiles

by Brendan Edwards and Ella Heiss

This curatorial essay was written for Textus-Texts-Textiles, an exhibition at W.D. Jordan Rare Books and Special Collections, Queen's University Library. Used with permission.

CON•NEC•TION

by Rebecca Korn

This curatorial essay was written for CON•NEC•TION: Forty Years of Artist's Books, a retrospective exhibition. Used with permission.

Body Map: Reclaiming the Artist's Body

by Rebecca Korn

This essay was written for ARTH3100/Fall 2019, Carleton University. Used with permission.

Lise Melhorn-Boe: RE Books

by NO and NO

This interview was commissioned by Modern Fuel-Artist-Run Centre to accompany the May 2017 exhibition in the Flux Gallery at MFARC. Used with permission.

Harvesting Environmental Justice: The Bookworks of Lise Melhorn-Boe

by Heather Saunders

Telling and Retelling: Some Remarks on the Bookworks of Lise Melhorn-Boe

by Gil McElroy

Past Lives

by Joan Murray

Creative Meaning-making

by Tara Hyland

Home/bodies

by Carolyn Langill

Fairy Tales and Family Fables

by Tara Hyland-Russell

Sometimes You've Got to Wake Up the Frog

by Tara Hyland-Russell

Textus-Texts-Textiles

Brendan Edwards and Ella Heiss

Brendan Edwards is the Curator at W.D. Jordan Rare Books and Special Collections, Queen's University Library, in Kingston, Ontario. Ella Heiss is a student in HIST212, Experiential Learning in Historical Perspectives, Queen's University.

Used with permission.

Threading the Needle

Textus-Texts-Textiles explores the relationship between texts and textiles, through a feminist lens, via the sewing bookworks of Kingston artist, Lise Melhorn-Boe, supplemented by books as cultural texts and technological artifacts from the collections of W.D Jordan Rare Books and Special Collections.

TRANSF., (1) to twine together, intertwine, plait…; Verg. (2) to put together, construct, build…; Verg. (3) of speech or writing, to compose…

textĭlis -e (texo), woven, textile… Also plaited…

textus -ŭ, m. (texo), a web; hence texture, structure: Lucr. TRANSF., of speech or writing, mode of putting together, connexion…

The word ‘text’ derives from the Latin texěre or texo, ‘to weave,’ while ‘textile’ comes from the Latin adjective textĭlis, meaning ‘woven,’ which stems from textus, the past participle of the verb texěre. Thus, in naming this exhibition Textus-Texts-Textiles, we are riffing on the idea of the act of weaving meaning that authors, artists, and poets engage in, but also the layered paratexts, the meticulous threading or stitching together of fabric in the labours of a seamstress or seamster, and the methodical travails of the printer and bookbinder. Text is a formal utterance of speech, and texts can be thought of as transactions in meaning. The ‘book,’ which is frequently understood as shorthand for many forms of written textual communication, is an interdisciplinary medium that can be conveyed by physical forms that vary to a great extent. The meaning of the book is not fixed in material, history, or format. This is one task of the book historian and bibliographer, to uncover the social and political roles ascribed to books and their texts, and how these relate to the reception and use of the form of the book as a communicator, container, transmitter, manipulator, and instrument of memory. The Latin, textus, suggests a link between text and tangible object, wherein the substance of the object is differentiated from the object itself. Thus, textus adjoins the idea of weaving or stitching together words to express an idea and communicate–texts–with the weaving of fibres to create a tangible object that itself tells a story, and upon which a story can be told–textiles. The sewing bookworks of Melhorn-Boe encapsulate this sentiment in literally and figuratively weaving/stitching together stories, texts, and fabric to express the ideas of poetry which itself draws upon the metaphors of threading, sewing, and needlework. As multidisciplinary writer and artist, Caroline Langill observed in 1999, “For Melhorn-Boe, the form of the book becomes an object of investigation/contemplation quietly offering surfaces, textures and layers through which the texts are woven.”

Stitching Together MeaningsMelhorn-Boe has been making books as a medium of art for more than forty years, drawing from women’s experiences in the political and personal spheres with “humour and a light-hearted visual aesthetic to explore more serious feminist and environmental issues.” As Melhorn-Boe explains, “This series started out as an exploration of poems in Lorna Crozier’s book The Book of Marvels: a compendium of everyday things…” and through an organic curiosity, it grew to include the works of other poets, including Terry Ann Carter, Hazel Hall, Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson, Diane Dawber, Alexandra Cussons, and Bronwen Wallace.

The traditional book is a vessel of power and information. Since its inception, it has been a determiner of what a society has deemed important to record, publish, disseminate, and preserve. The book also reveals what is undervalued or ignored in what is absent, what has not been written, published, dispersed, or collected. On the whole, artists’ books ask their readers to “contemplate all parts of a book as capable of communicating meaning and to redefine the functional potential of the book as a medium.” Artists’ books also draw on the idea of the book as a recombinant structure, showcasing form and allowing the reader/viewer “to create new juxtapositions within it.”

Melhorn-Boe’s sewn books, and her choice of poetry, consider the silences of female voices suppressed by sexism, and the layered meanings behind ‘women’s work.’ Traditionally, the book has been a means of establishing and maintaining power in society by influencing the minds of readers. Even the ability to read is a form of power that impacts how a society operates. The literary canon, and the history of writing, printing, and publishing overall, have historically been predominantly male–from which books were (re)printed, to which authors were studied, and to which rare and antiquarian books have historically commanded the highest prices. Not only has the history of the book been largely shaped by men and masculinity, but it has also heavily influenced cultural and historical perceptions of masculine and feminine cultures. Melhorn-Boe bestows power to her readers by intentionally leaving room for interpretation of her work through visuals and tactility, while simultaneously offering the audience a guide of where to go. The act of reading and drawing meaning from one of Melhorn-Boe’s textile bookworks is an act of reading beyond words, where the tactility and material form of the works, the fabrics and threads from which they are constructed, their shapes, colours, and design, express as much thought and meaning as the texts themselves. Through deliberate choices in relation to poetic and material content, Melhorn-Boe’s fabric bookworks can be interpreted as reclaiming what has been historically moderated by men. A deliberate infusion of feminist theory and imagery has been an underlying theme for more than forty years in Melhorn-Boe's art.

In the series of bookworks presented in this exhibition, “It all begins with text, a poem that speaks to the artist, which she then materializes into an artist book.” All the poets showcased in Melhorn-Boe’s fabric bookworks are female writers who speak to gender roles, sewing, textile arts, and femininity. In imagining and crafting material representations of these poems, Melhorn-Boe reminds us that handmade books, in their plethora of forms, are vessels of humanized content, or what might be thought of as “touchstones of what we are as people.”

The exhibition is organized in the chronological order that Melhorn-Boe created each work, to reflect the artist’s continuity and development of thought. Lorna Crozier’s collection of poetry, The Book of Marvels: A Compendium of Everyday Things, is placed at the beginning as it served as the first inspiration for this series of fabric books. Crozier’s poetry considers the psychological relationship between objects and words. Although she had used a suite of Crozier’s poems (Sex Lives of Vegetables) to create an artist’s book of the same name in 1990, Melhorn-Boe first met Crozier at the Kingston WritersFest in 2015. Crozier suggested that Lise might like to ‘play with’ the poems in The Book of Marvels, which ultimately led to Button, Melhorn-Boe’s interpretation and physical realization of the Crozier poem of the same name. The buttons utilized in this work are each embedded with meaning, inherited by Melhorn-Boe from the sewing materials of several women, including her mother, ex-husband’s grandmother, and a friend who had moved into a nursing home. Unlike the solipsistic character of the button in Crozier’s poem, Melhorn-Boe has infused this work with the experience of others, emitting objectivity and selflessness. Such themes are evidently weaved throughout all the works in this series, of the interrelationship and interconnectivity of human experience, but also the ways in which everyday items can be imbued with meaning.

Zipper, also inspired by a Crozier poem of the same name, was the second creation in the series, and it would ultimately be the impetus for Zipper: A Suite with a poem by Terry Ann Carter. Melhorn-Boe and Carter met at Minotaur, a downtown Kingston games, gifts, and crafts store where Lise worked for several years, when Carter was in town to teach a haiku workshop. When they realized that both were members of CBBAG (Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild), Melhorn-Boe and Carter exchanged website URLs. The next day, Carter spent time in Melhorn-Boe’s living room looking at books and ultimately buying a copy of Zipper. Inspired by reading Zipper in Lise’s living room, with a painting by Sharon Thompson on the wall, Terry Ann composed ‘Zipper: A Suite’, the physical realization of which would become the third bookwork in this series. Zipper: A Suite, is the sole instance in which Carter’s poem has been published to-date.

In the meantime, Melhorn-Boe was already working on Needle, inspired by a Crozier poem of the same name. In Lise’s words, “It made sense to me to make the book look like a needle book.” Needle-books, which are needle-cases made of cloth or flannel with leaves and covers resembling a small book, have an origin dating back to at least the 17th century. Needle books have often been objects of adornment, frequently embedded with motifs or embroidered messages for/between female friends.

Terry Ann Carter introduced Melhorn-Boe to the poet Hazel Hall (1886-1924), whose writing focused significantly on sewing and needlework. From the age of 12, Hall was bound to a wheelchair and spent most of her life sewing in an upstairs room at her family home in Portland, Oregon. Hall found deep meaning in inanimate objects, often perceiving them as an extension of herself. Reading Hall’s poems stirred Melhorn-Boe to expand this series beyond the work of Lorna Crozier.

For this series, Melhorn-Boe made a conscious effort to avoid buying any fabric, instead using materials from her own stash, as much as possible, or from the stashes of friends. Mending and Counterpanes were the first works inspired by the poetry of Hazel Hall. In imagining and creating Mending, Lise reached out to women in the Organization of Kingston Women Artists (OKWA), requesting old clothing that needed mending, and received an enthusiastic response. The copy of Mending on display in this exhibition has, as covers, pants belonging to Sharon Wightman, a graduate of the Queen’s University art conservation program and former volunteer at the Queen’s University Archives. The dress shirt belonged to the husband of a friend who was looking for an excuse to clear his closet. The pyjama pants and wool gloves belonged to Lise herself (“those gloves had been mended so many times!”), while the Lunenburg Folk Festival t-shirt came from Wendy Cain’s stash of cotton clothing saved for for paper making. Lise contextualizes, noting, “I have never been to that festival, but I have been to Lunenburg many times as my mother grew up in Lunenburg County.” The notion evoked in Hall’s poem, of “strengthening old utility, pending the coming of the new,” is realized in form in Melhorn-Boe's re-working and re-purposing of discarded garments, and in how she has stitched together the lived experiences of several women.

Counterpanes, stimulated from a Hazel Hall poem of the same name, was designed as a meander book that opens to resemble a quilt. Meander books (sometimes called ‘maze’ or ‘puzzle’ books in the bookmaking community) are a structural variation of the concertina or accordion fold book and get their name from the way a single piece of paper has been cut and folded to make pages–in a so-called meandering format. Meander books unfold in a variety of ways and are thus a kind of intellectual puzzle that require careful attention to layout. Lise has taken the meander book model and fused it with that of quilting, itself a means of representing narrative in many cultures and instances. Quilting, much like Melhorn-Boe’s overall approach in the sewing bookworks series, involves a form of visual literacy where every piece of fabric and every stitch matters, and every quilt is the sum of its parts. A sense of meandering, of seeking and quilting together renewed security and shelter, is one possible interpretation of Hall’s poem.

In her search to identify additional poems about sewing, Melhorn-Boe came across Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson’s, “I Sit and Sew.” Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935) was an American poet and suffragette. Her work reflected the Black female voice of her era and challenges to femininity. Notably, Dunbar-Nelson also utilized the book arts as a form of expression, creating scrapbooks chronicling her experience as a travelling speaker on suffrage. Like the act and labour of sewing, external perception is just as impactful as the meaning behind the act itself. “I Sit and Sew” is Dunbar-Nelson’s reflection on World War I, commenting on the fruitless task of a woman limited to merely sewing throughout the horrors of war. Melhorn-Boe was thus inspired to model I Sit and Sew on the physical structure of an early 20th-century soldier’s sewing kit, known as a huswif or ‘housewife.’ This meaning of ‘housewife’ seems to have originated in the mid-18th century, with the word itself deriving in the 13th century from husewif (Old English huse meaning ‘house’ combined with wif meaning “woman) and eventually evolving into popular vernacular and an association with femininity. The ‘housewife’ was a compact sewing kit originally made of cardboard or cotton cloth, holding needles, thread, buttons, and pins. Soldiers used the kits to make quick repairs to their uniforms and general upkeep of their look. During the American Revolutionary War, for example, sewing was perceived as a woman’s way of contributing to the war effort and sewing kits became a reminder of womanly care for soldiers on the front. During both World Wars, sewing was likewise delegated to women as a means of contributing.

Grandmother is Melhorn-Boe’s iteration of a poem by her friend, Diane Dawber, a Kingston poet. This work uses bits of strip-piecing (typically utilized in a patchwork quilt-making technique) that Linda Coulter, a member of a small local textile group to which Melhorn-Boe belongs, offered up when she didn’t need them anymore. Like Mending, with its covers made from a pair of pants, Grandmother features covers made from a pair of seersucker shorts; others in this edition feature madras plaid shorts acquired from a second-hand store, a direct nod to the woman in the poem who shopped at rummage sales, then ripped out the seams of her finds, to inevitably sew new patterns. These fabrics fit the period of the poet, Diane Dawber’s, childhood, and Coulter’s trove of strip-piecing provided ample fabric to make pages that coordinated colour-wise with each pair of shorts.

Another poem by Lorna Crozier was the root source for Ironing Board. Melhorn-Boe describes making the little clothes that sit on the ironing boards as taking her back to her childhood when she sewed doll’s clothes. The ironing boards have a plywood base, salvaged from the lining of shipping boxes from the Japanese Paper Place; Melhorn-Boe saved them from origami paper shipments during her time working at Minotaur. The act of re-using, re-purposing, and re-imagining new uses for what otherwise might be thrown-away, discarded, is a theme that Melhorn-Boe has reflected upon many times throughout her career, and this practice also further embeds each of her bookworks with depth and meaning. The act of re-using is apparent in Crozier’s poem; with each re-use of the shared hotel ironing board, layer upon layer of story is applied, leaving permanent traces.

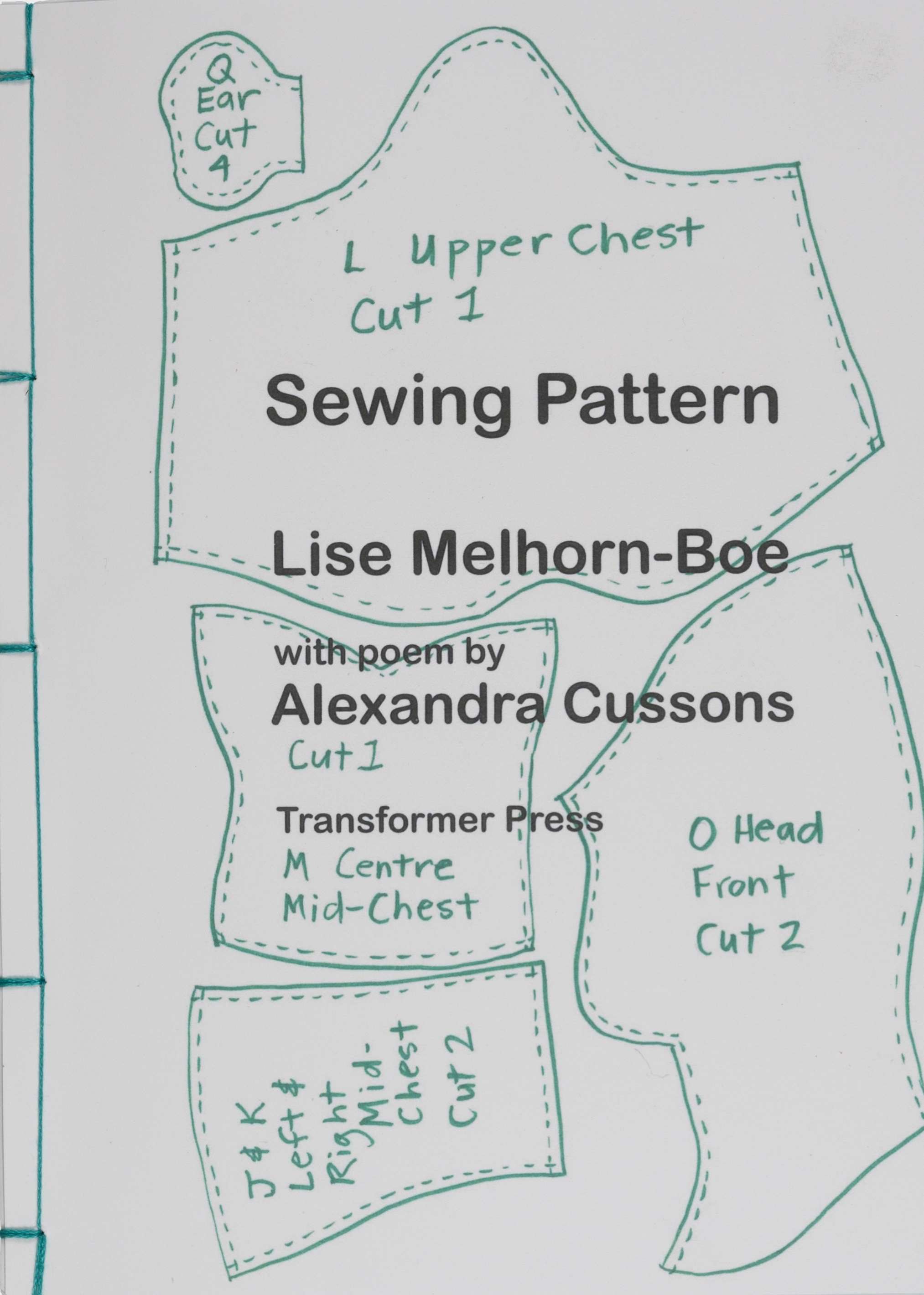

Sewing Pattern, the only book in this series which, at first glance, is not noticeably constructed of fabric, is based on a poem of the same name by Alexandra Cussons, a 2011 Foyle Young Poets of the Year award-winner. Printed on Canson Infinity Rag paper and rag vellum, with a sewn stab binding, Sewing Pattern is presented as a pattern book, featuring templates of pattern pieces, and hand-illustrated sewing instructions to create a woman. Rag paper and rag vellum (a term used to describe high quality rag paper with a smooth surface imitating traditional vellum) are made using cotton linter or cotton derived from used cloth rags. While most paper today is made from wood pulp, cotton rags were the primary source material in papermaking from 105 CE through the 18th century, thus many of the earliest printed books on paper have a direct relationship to textiles. Sewing patterns have appeared in print, in books, manuals, and magazines, from the 16th century, reaching a height of popularity from the mid-19th to the mid-late-20th centuries. Before the popularization of the sewing machine and ready-to-wear clothing, the pace of fashion relied on the manual creation of garments; magazines marketed to women in the 19th and 20th centuries frequently featured sewing patterns, with the aim of giving women direction in making their own clothes. Patterns on paper were often suitable for just one use, as the thin paper on which they were printed could easily distort or tear during use. This inherently ephemeral quality is hinted at in Cussons’ poem.

Another Hazel Hall poem inspired Two Sewing. The nature imagery in the poem invokes a landscape, inspiring Melhorn-Boe to utilize the tall, skinny format of a flag book–an accordion or concertina structure with tipped on pages at different levels, so that when the book is open the pages act as flags–which open into a landscape. With its delicate satin-stitched tulips and crocuses, Melhorn-Boe has stated that this book was the most technically challenging of the series to make.

Heavy Threads is based on a Hazel Hall poem, which Melhorn-Boe states, “attracted me because it reminded me of a poem my mother wrote”:

This is how I felt at 11:30 a.m., May 3, 1983.

I am surrounded by army antsWho nibble at my time

and disturb the mould of my life.

Each night I lie in the dark and plan paintings,

write poems and draft stories.

In the morning they begin.

Their chewing proboscises take the form of telephone calls,

lost objects, loud voices, disturbing thoughts.

Incompetencies.

I empty the garbage, prepare the noon meal,

Wash a few clothes,

Gnash my teeth.

The poem is lost, the painting never reaches canvas or paper,

the story outline vanishes.

Only left is a tiny pile of dried thoughts

which crumble and blow away.

My heart contracts, my muscles tighten, I choke on my own bitterness.

Maybe tomorrow will be better?

But they will be back, the army ants,

to nibble and chomp.

In 10 days I will be fifty-nine,

and will fade away and no one will ever know

what excitement and joy might have lain in

those tiny piles of nothing dust.

-- Pauline Gillmore Melhorn

Heavy Threads is assembled in a star carousel structure with ribbon closures. Just as Hall’s poem begins with imagery of ribbon thrown through a window, the star book format of this work opens to reveal a series of windows that frame a range of colours and ribbon-like slashes. The hand-painted fabric in this work is by Melhorn-Boe, a leftover from her grad school days at Wayne State University, and the work also features fragments from delicately embroidered placemats and matching napkins and other fabrics from Melhorn-Boe’s stash.

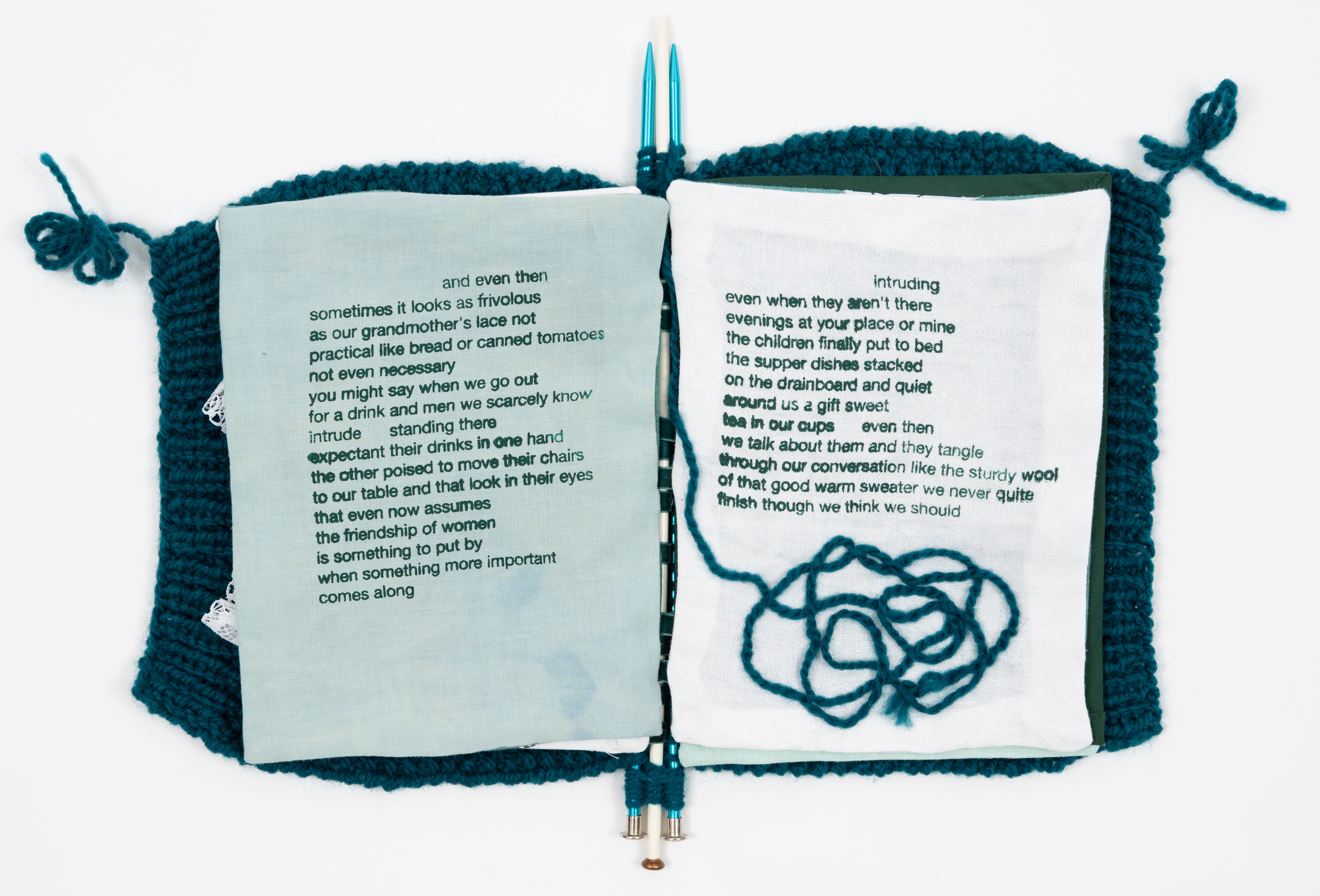

The final work in the exhibition, Like the Petit Point, is Melhorn-Boe’s interpretation of the Bronwen Wallace poem of the same name. Wallace (1945-1989), a Kingston local and Queen’s University graduate, was an advocate for women’s rights who focused her work on feminist issues surrounding domestic violence and sexual discrimination. The poem refers to books read, thus Melhorn-Boe has recreated the covers and title pages of pioneering second-wave feminist books in the pages of Like the Petit Point, utilizing knitting needles to form the spine of the book. While designing this work, Melhorn-Boe would discover that many of the landmark 1970s feminist books she wanted to reference were not available at her local public library, prompting her to ask, “How are young women of today supposed to learn about feminist history if the books are not available?” As with other books in this series, the text has been screen-printed with screens made on a 3M Thermo-Fax machine. Introduced in the 1950s and discontinued in the early 1990s, this seemingly outdated piece of technology was a thermographic printing system. Some contemporary artists continue to use the thermo-fax machine and similar copiers in riso printing by textile artists and printmakers, and by tattoo artists to create stencils. The petit point image (a type of canvas embroidery) within the book is deliberately unfinished, just as Wallace’s poem mentions putting a project aside when other work intrudes, or something seemingly more important comes along.

Choice or Chore: Women and Stitching

Melhorn-Boe used a variety of fibre and textile arts, such as sewing, petit point, and embroidery to create these bookworks. Traditionally, sewing, textile, and fibre arts have been associated with femininity and ‘women’s work.’ The European Industrial Revolution mechanized sewing and made it the highest paying and accessible job for working-class women, creating a ‘pink collar’ industry. The sewing machine encapsulated the effect of non-human actors in history, a trend that has dramatically increased in the centuries since, nowadays encroaching on almost every aspect of our lives. Owning a sewing machine gave women the opportunity to dictate the course and increase the scope of their work, however, gender roles frequently prevented women from acquiring high volumes of work. Despite the sexist connotations, sewing was an outlet of feminine freedom as it supplied women with income and the ability to express themselves creatively.

In the early 20th century, as more women began to enter the workforce due to increased industrialization and WWI, sewing became either a choice or a chore. With the popularization of ready-to-wear clothing, sewing was, for many, no longer a necessity, rather a craft. Sewing as a choice or chore was, however, dependent on one’s level of income; wealthy women could afford to create elaborate garments and accessories, versus the working-class woman who sought cheaper, practical clothing. Geography too could determine the amount of sewing a woman might engage in, as rural women often had less access to shops with ready-to-wear clothes. While working women were encouraged to sew to clothe their families, they were discouraged to partake in decorative crafts such as embroidery and crochet as these were frequently portrayed as frivolous and unnecessary. Sewing would also become paradoxical in nature as one might assume that wearing handmade clothing meant one was poor (consider the lyrics of Dolly Parton’s song, “Coat of Many Colors”), while sewing for leisure was associated with the upper-classes.

The stereotype that sewing and textile arts are feminine was further perpetuated by marketing and education, emphasising home sewing as a form of domestic care and “motherly love.” Melhorn-Boe’s bookworks embody the feminine ideals of sewing in an empowering way that highlight the contributions ofShe was an advocate female artists and their affinity for domestic crafts through her choice of poetry and use of a variety of techniques. Going well beyond the act of crafting a practical garment, Melhorn-Boe’s sewing bookworks embody multiple layers of meaning, intuitively and creatively stitching together texts and textiles, while subversively asking her audience to read beyond the text and to scrutinize sewing as ‘women’s work.’

Tying it All Together

Textus-Texts-Textiles encapsulates the relationship between tangible objects and the written word through the medium of book art. Just as one weaves fibres together to create a textile, or stitches fabrics together to craft a piece of clothing, words are woven and stitched together to express complex ideas. There is a foundational relationship between texts and textiles in that they both hold power and meanings communicated through a visual medium. From the sewing machine of the Industrial Revolution, to WWI sewing kits and beyond, women have been directly associated with sewing. Melhorn-Boe's strategic selection of female authored poems is a comment on the institutionalised gender biases within society. Book arts in general can be paradoxical in nature, as both a private and public presentation of ideas. In her sewing bookworks, Melhorn-Boe utilizes materials from her private life, such as clothing, fabric, buttons, and thread, to publicly textualise ideas on feminist issues and gender stereotypes. She pulls threads from her own experiences and then stitches them anew to highlight her perspective on how women are stereotyped into domestic crafts as a chore, thus reclaiming the creative and empowering aspect of the practice.

CON•NEC•TION

noun: A relationship in which a person, thing, or idea is linked or associated with something else

Rebecca Korn

Rebecca Korn is a fourth-year undergraduate student at Carleton University in the department of Art History, set to graduate in August of 2020. She was awarded the Jack Barwick and Douglas Duncan Memorial Scholarship for Art History in her third year, as well as a Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences research internship over the summer of 2020. SHe has been awarded three scholarships to pursue an M.A. in Art History at Carleton in September of 2020..

Used with permission of Rebecca Korn.

Lise Melhorn-Boe is a contemporary Canadian artist currently working in Kingston, Ontario. Having received M.A and M.F.A degrees from Wayne State University in Detroit, Melhorn-Boe has exhibited across Canada, the United States, Europe and South America throughout her career. Melhorn-Boe’s oeuvre reflects her feminist beliefs, often calling for viewers to reconfigure their conception of social normality. Techniques and media such as textile work, stitching and sewing, are employed by the artist to call attention to feminist concepts, countering the historically categorized modes of sex and gender. Also encountered in her oeuvre is environmental theory. Concerned with the increasingly diminished health of the environment and the effects of this that individuals encounter, Melhorn-Boe calls attention to the increasing disconnect we have with our planet.

Creating something with one’s own hands lends itself to an infusion of the producer into the product. Art, if honest and vulnerable, can become a reflection of the artist. This is where Lise Melhorn-Boe thrives. Her work focuses on a plethora of things important to her, including ideas of gender and its societal stereotypes, the effects of the increasingly polluted environment, the human body, family, and most recently, her sewing works. Despite varying in theoretical focus, her handmade artist books all share a common thread by means of providing physical, tangible access to the artist’s personal connection to the given subject. My previous relationship to Melhorn-Boe entailed our working together for the better part of five years. Still, I never quite knew the details of her life outside of our working relationship. While planning for my essay, however, I was invited to her blue living room to discuss her art and read her artist books. I was subsequently granted a glimpse at what drove the artist to produce art throughout her career, and what events and thoughts made her who she is today, as both an artist and as a human being.

As I moved through her works, the first theme that jumped out at me was that of family connection, and I believe that this theme is one that many of us can relate to. Prominent examples of her work that relay familial connection would be Ghost Costumes (Kurt) and Ghost Costumes (Pauline) both from 1996-7, with Kurt being the artist’s father and Pauline being her mother. These are unique works that recall the artist’s parents and their lives through clothes they have worn often, for work or other occasions. Melhorn-Boe crafted each garment as a replica of clothes worn by her parents throughout the years of their lives. The variance between Pauline’s and Kurt’s sets of replica garments resides in the use of words in Pauline’s set and the lack thereof in Kurt’s. Within this difference, feminist theory operates.

Each garment in Ghost Costumes (Pauline) is layered with words transcribed from a taped interview with Pauline. Reading the words through the sheer fabric presents the viewer with multiple connections to the artist’s mother. Through the chronological reading and viewing of this work, the viewer is confronted with the reality of socially structured gender roles. In mid-late twentieth century Canadian society, women were expected to wear dresses, silence their opinions and above all, be a mother. In this work Melhorn-Boe liberates her mother’s words, expressing personal frustrations and desires that were too often silenced by society. This being said, the feminist underpinning of these works shines brightest when the two halves are experienced together.

Ghost Costumes (Kurt) provides a stark contrast to Pauline’s set of garments and reflects Melhorn-Boe’s father’s career as an electrical contractor. Where the artist had used gauzy fabric for her mother’s garments, for her fathers she chose a sturdier, unbleached muslin fabric to recreate his work garments. Immediately the contrasting fabric choice recalls the dirt and grime encountered in his daily work life. This work does not include any writings, only photographs of construction sites and substations. This substitution of words for photographs persuades the viewer into thinking of Kurt solely as a hard worker whose role in society is to provide for his family. Both Kurt and Pauline are positioned in these works by Melhorn-Boe to reflect the static gender norms of the society in which they lived. The artist is not suggesting that either struggle is dismissible, rather she is citing the traditional roles men and women were required to play in late-twentieth century Canadian society. The inclusion of personal familial information in these works requires a certain sense of vulnerability inherent to Melhorn-Boe’s oeuvre.

Her vulnerability is not reserved solely for large life events. Experiences explored in her works also include small events, such as the meals that the artist’s family had enjoyed. For instance, her 1982 work Light and Flaky recalls the format of a recipe book with ingredients and instructions included. Juxtaposed with each recipe is a story about the foods made by Pauline and enjoyed by the family. The stories are exceptionally told—reading through them, you can nearly see her mother Pauline cooking and her father Kurt hiding cakes in his filing cabinet. Her 1998 work The Family That Liked to Eat also discusses the family’s connection to food, and how they bonded over delicious meals. The focus on food in a selection of Melhorn-Boe’s works about family serves as a gentle reminder that sometimes a connection can be modest. For example, you and I can have a simple conversation about our favourite meals, what we ate growing up, or our favourite childhood candy, and have a connection to each other through that. However, not all connections are quite so modest.

On a larger and more confrontational scale than her family-themed works, her environmental works call their viewers’ attention to ongoing environmental issues. Her 2006 piece titled No Safe Levels employs the medium of watercolour on acid-free paper and discusses both the detrimental effects of pollution on the human body and the artist’s understanding of and connection to the environment. Inspired by the rock-cuts at the sides of highways in Northern Ontario and Québec, No Safe Levels depicts a paper pop-up representation of rock cuts which simultaneously morph into the artist’s body. The rock cuts are not natural but rather they were built to provide industrial access to natural resources such as minerals. The unnatural beauty of these rock forms is something the artist is drawn to despite being cognitive of their industrial origins. This work provides new insight in tandem with the environmentalism dialogue in which other artists partake in as well. For example, Edward Burtynsky’s large environmental photographs similarly dissect the effects of industry on the environment, yet they do so on a macro scale. Where his photographs dismiss the immediate presence of people, they depict the effects mankind has on the natural world by displaying industrial landscapes such as mines and quarries. Melhorn-Boe’s work No Safe Levels similarly depends on the intertwining of mankind and the environment, only she comments more so on pollution’s impact on one individual body. Where in Burtynsky’s photographs the viewer is confronted via the scale of his work and the clarity of their devastating depictions, Melhorn-Boe’s environmental work confronts the viewer more individually. As individuals we are affected by what Burtynsky’s photographs show so clearly; the mass production of pollution and devastation of the natural world. Melhorn-Boe’s work relays the direct impact of Burtynsky’s industrial landscapes on an individual body. Ultimately, No Safe Levels is claiming that individual body and environment are one. Only when the latter is realized can we truly begin to halt and reverse our abuse of the environment. The artist’s keen attention to the health of the environment is exemplified further through her use of hand-made and recycled materials.

Melhorn-Boe’s thoughts about our modern societal disconnect from the environment are subtly but effectively articulated even through the materials used to create the works. The artist’s drive to reuse and recycle is inherent to these works. Many of them are made from paper she created by hand. She learned how to make paper, along with many other skills, when she began her Master of Fine Art program at Wayne State University in Detroit in 1980. For the artist, making paper by hand is a transformative process which involves taking old clothes and making them into functional and beautiful paper. Portrait of the Artist’s Family (1980) is an example of this: after asking each of her family members to gift her an article of clothing, Melhorn-Boe collected them all and made them into paper. Each family member has a page made out of the clothes they donated for the work, on which is written their name, not only to acknowledge them as members of the artist’s family, but to connect each person to the work itself and the viewer reading it. This memorializing of her family on recycled paper is an important link between Melhorn-Boe’s exploration of family connections and her exploration of our connection to the environment.

Also visible throughout the artist’s catalogue are artistic studies of her mind and body. Never have I met a more mindful individual, in terms of both environmental sustainability and her understanding of her body. Contemporarily, individuals seem to be losing the sense of their own bodies as standards of beauty, and the made-up rules and regulations on desired body types continue to fluctuate between poles. But do we truly understand our own individual bodies? This is where Melhorn-Boe’s brave sense of vulnerability becomes increasingly evident. In her 2009 work, Body Map, she uses photographs collaged by computer to create a head-to-toe image of her own body, in order to truly demonstrate what it means to be in touch with one’s body. Body Map also discusses society’s regulations on what it means to be feminine or masculine. Her strategic placement of the collaged body parts in a body-builder pose comments on and critiques many stereotypical assumptions about femininity—women can be strong, and this strength can be mental, emotional, or physical. While the photos of her body are arranged into the silhouette of a classic body-builder pose, the entire work retains the form of an artist book. The pages do fold up, and feature hand-printed lettering on their surfaces that outline personal information concerning the health issues she has encountered throughout her life. This work is a strong example of how important the connection between body and mind really is. Understanding one’s own body leads to understanding one’s surrounding environment, which in turn leads to an even greater understanding of the body, thus entangling the two into a state of general mindfulness. This work recognizes many of the artist’s personal struggles, including environmental stresses on her body, her battle with breast cancer, and smaller concerns such as spider veins. Not only does this work recognize her fundamental connection to her body, but it also portrays the artist as purely human. Sometimes, when looking at art, it can be easy to forget about the essential connection the art has to the artist; even art created five hundred years ago still retains its maker’s touch. However, Body Map makes it impossible to overlook this essential principle of art. This work exposes the artist in various ways to its viewers, inviting those that see the work to see the artist, and to feel a sense of connection, and it hardly matters whether this connection is based in similar experiences, sympathy, or understanding. Instead, what matters is the artist’s ability to be open enough to welcome a connection with the public and its gaze.

Melhorn-Boe’s newest sewing works constitute another series that demonstrates similar themes to Body Map by discussing gender roles. Her latest book, called I Sit and Sew, is about the First World War, and combines gruesome images of the fundamental nature of war with fine stitching. I Sit and Sew is her endeavour to materialize a poem by the early 20th century American poet, Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson. The poem refers to the frustration of one woman who wanted to take a more active part in the war rather than sitting and sewing but was limited due to societal expectations concerning women’s role in the war. Melhorn-Boe also watched Peter Jackson’s documentary, They Shall Not Grow Old, which features old WW1 footage from the British Imperial War Museum. Initially, the artist hoped to use photographs of injured and deceased soldiers but decided upon reflection that this would be uncomfortable as she has no connection to the men in the photos. Instead, she decided to draw images and stitch them. The work’s form is modelled after sewing kits carried by soldiers which were called “housewives”. Some fold out into a line, some are formed in a cross shape, but all can be folded small enough to fit into a pocket or bag. This moniker calls attention to the many housewives who were put away in their homes to look after children and to be available for their husband’s use.

I Sit and Sew also retains a strong, fundamental connection to the artist’s family that can be found throughout Melhorn-Boe’s oeuvre. Specifically, in regard to this work, her grandfather was in the trenches in the First World War, and her mother was in the Air Force in the Second World War. This generational gap shows the improvement of societal views on acceptable roles for women. However, in the mid-1910s, the period for which this work focuses on, women were expected to be domestic beings. That said, I Sit and Sew highlights both the struggles women faced while pushing for their right to contribute to the war effort, and the loosening of societal restraints on women between the First World War and the 1940s. Further, the fine stitching included in this work shows the struggles women faced in the art world throughout history. Many women struggled to be taken seriously as artists, despite being as capable as their male counterparts. Consequently, many of them chose sewing and tapestry-making as opposed to joining the male dominated art sectors such as painting and sculpting. For Melhorn-Boe to use the medium of sewing and fine-stitching in her own way is a statement of the times, a statement on a more open art realm and its contemporary ability to see beauty in objects and works that differ from traditional painting and sculpture. Combining war images with a poem that outlines a woman’s struggle to provide effort in the war and the beauty of the medium of sewing dismisses constraints previously put on artists and, furthermore, on women in the world at large. I call attention to this work because these complex, beautiful, and empowering ideas are all well thought out, and act as a testament to Melhorn-Boe’s research and preparation before works are materialized. It all begins with text, a poem that speaks to the artist, which she then materializes into an artist book. I Sit and Sew fits into her forty-year-old oeuvre without a hitch.

The element of physical connection is inherent to the very nature of artist books; to view and experience some of Melhorn-Boe’s works, viewers have to physically open them and flip through their pages. Works such as Zipper: A Suite (2019) and Button (2018) invite viewers to become active participants. In order to really grasp these works, viewers have to experience the work in time by respectively unbuttoning or unzipping each page to reveal the text. Zipper: A Suite is a collaborative work that uses Terry Ann Carter’s suite of five poems written in response to viewing Melhorn-Boe’s previous work, Zipper (2018), which also has to be unzipped to be read. The imagery used in Carter’s poems had excited Melhorn-Boe to make a bookwork using them, and for good reason. One of the poems calls attention to “a room coloured cobalt-blue” and the abstract painting by Sharon Thompson on the wall. Having recreated the painting for the bookwork, the artist provides the book’s viewers a visual experience to accompany the words written by Carter. Thus, by viewing the work and participating via unzipping the pages to reveal the text, the artist, poet and viewer are tied through the experience of the work itself. The connection between two artists is then amplified by a connection between artwork and viewer.

Lise Melhorn-Boe’s work asks hard questions, provokes tough societal conversations, and portrays the importance of human connections. These connections range from familial to environmental, but all are crucial to the artist and her work. The vulnerability and honesty inherent to her works show her as artist and human alike, providing an open window into the artist’s thoughts, making it easy for viewers to connect to both the work and artist. After spending months reading and appreciating her works, I have learned that, more than anything, the connections one can make in this life are what we will be defined by when no longer here. Whether these connections are with friends, family, lovers, the planet, oneself, or even our four-legged furry friends, we will only be remembered if we are open to connections. The beauty of Melhorn-Boe’s work is that her works are complex in thought and technicality, they are witty and yet serious, and each one invites connection between artist, work and viewer.

Body Map: Reclaiming the Artist's Body

Rebecca Korn

Rebecca Korn is a fourth-year undergraduate student at Carleton University in the department of Art History. She was awarded the Jack Barwick and Douglas Duncan Memorial Scholarship for Art History and is planning on doing an M.A. in Art History focusing on Italian Baroque Art.

Used with permission of Rebecca Korn.

Although feminism is a fairly modern term, women artists throughout history have been largely dismissed from the canon. The systematic limitations that caused this dismissal have also trickled into our modern era. Historically, women artists have been dismissed from the canon of art history due to systemic social control such as the inability of women to enter academies and study from nude male models. For example, before 1897 the Ecole des Beaux Arts in France excluded women entirely. The next generation did not provide women artists with many more opportunities. Although modern art carries the connotation of going against the academic grain, women still were left out of the formation of artist’s groups in the early twentieth century. This is because many modernist groups found their beginnings at places that women were still prohibited from such as the Academy, or in salons. The few schools that did offer women an education in the arts often focused on decorative arts and tuition was sometimes doubled compared to that of their male counterparts. Due to the evident limits placed on women throughout the history of art, I argue that even contemporary women artists are continually required to find creative ways to resist these limits. As Griselda Pollock states “feminist interventions have to disrupt canonicity and tradition” and I believe Lise Melhorn-Boe does just that. In her work Body Map (fig. 1), Melhorn-Boe reclaims what has been historically moderated by men in the art world; the female body.

Lise Melhorn-Boe is a contemporary Canadian artist who infuses her works with activist and feminist theory. In her 2009 work, Body Map, she used photographs and digitally collaged them together to create a head-to-toe image of her own body. Her strategic placement of the collaged body parts in a bodybuilder pose comments on and critiques many stereotypical assumptions about femininity. The artist here is countering stereotypes and saying that women are strong, and this strength can be mental, emotional, or physical. The construction of Body Map as a collage of images of her body also echoes the way in which female bodies have been visually received in art. Depictions of women in art that retain visual oddities, such as

The female body throughout art history has been manipulated to the point where idealization destabilizes anatomical correctness. An example of this would be the female body in Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ Grand Odalisque (fig. 2). There is no possible way that the model could have bent her legs and turned her torso in the way as depicted by Ingres. Here we see the historical bone-less preference of the female body in art. This idealization of the female body in art not only objectifies women but further distorts the very idea of the female body. This conception of the ‘perfect’ female body has been reiterated throughout historical literature and even mythology such as the story of the Judgement of Paris, where a man has the power to choose the most beautiful woman. To combat this excessive idealization and loss of individuality, Melhorn-Boe emphasizes her own individual body by hand-writing occurrences, injuries, and personal insecurities in relation to each body part.

Body Map features hand-printed lettering that outlines personal information concerning the health issues the artist has encountered throughout her life. This work recognizes many of the artist’s personal struggles, including environmental stresses on her body, her battle with breast cancer, and less threatening concerns such as spider veins. By highlighting the very things that make her body unique, the artist offers a unique view of the female body that differs largely from the canonical depiction of women as boneless and passive objects. Here the artist is depicting herself as artist and individual by emphasizing individual elements of her body. These elements, some more unique than others, allow viewers to see the artist as a real human, and one that many women can relate to. No woman can relate to the body without bones in Grand Odalisque, but many can relate to legs ridden with spider-veins and struggles with breast cancer. This work exposes the artist in various ways to its viewers, inviting those that see the work to see the artist, and to feel a sense of connection. It hardly matters whether this connection is based in similar experiences, sympathy, or understanding. Instead, what matters is the artist’s ability to be open enough to welcome a connection with the public and its gaze. This gaze, historically reserved for that of a male viewer, has been de-stigmatized through the artist’s detailed construction and presentation of a realistic female body.

Throughout Western art history, women have been the object of the male artist and thus, the male gaze. This is why when one walks through a gallery, one is bound to see a female nude. Men have time and time again depicted women in their art as naked creatures made out of pillows, chubby and soft and unbothered by the gaze of the viewer. Take Ingres’ Grand Odalisque for example. How do these women walk? They look as if they have no bones! Why do they all look the same, like some sort of human-pillow hybrid creature? Body Map further comments on this very depiction of the female body throughout the art historical canon by presenting the body of the artist unapologetically, unidealized and open to everyone’s gaze, not only the male gaze.

The female gaze has been patrolled by culturally structured norms. Women are often represented in art as subjects yet “their role as makers and viewers of images is scarcely acknowledged”. Melhorn-Boe combats this imbalance directly in Body Map by welcoming the gaze of the public. The female nude body has historically carried connotations of the viewer’s gaze as being privileged. This is because often nude female figures do not make eye contact with the viewer of the work, and when they do their back is turned to the viewer; lending the figure a sense of vulnerability. Melhorn Boe’s direct eye contact with the viewer subverts this historical expectation of the privileged gaze of the viewer. The gaze, and which gender has the ‘power’ to look, in terms of the arts has been culturally structured. Body Map presents to the viewer unavoidable eye contact with the artist (the subject of the work) which ultimately subverts the canonical and culturally-structured privilege of sight. Through confronting and acknowledging the viewers gaze, Body Map exhibits the artist and her reclamation of her gaze as female maker.

Although boneless depictions of females during the Renaissance may seem like lightyears away from our contemporary time, the historical systematic dismissal of women in the arts is still relevant today. As Griselda Pollock puts it “art history as a form of knowledge is also an articulation of power. What it says and what it disallows affects any living artist who are negated simply because they are women, a term art history has made antagonistic to that of artist”. By reclaiming her own status as women artist, and her reclamation of her female body from its historical objectification, Lise Melhorn-Boe resists the limits which have systematically been placed on women artists. Upon viewing Body Map and reading each of Melhorn-Boe’s real life struggles written over respective parts of her body, the viewer can immediately understand the artist as human rather than object. Her unavoidable gaze confronts the viewer, probing questions as to of why representations of the female often avoid the gaze of the viewer. No longer reserved for the pleasure of the male viewer, the female body of the artist is presented to the world as unidealized yet strong. The position of her body parts in a traditionally male pose further testifies this work as feminist; as pushing the cultural boundaries and limits placed on women.

Lise Melhorn-Boe: RE Books

NO and NO (Gabriel Cheung and Katharine Vingoe-Cram)

Written in 2017, for the exhibition, The RE Books, at Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre, Kingston, Ontario. NO and NO is a collaborative art practice and the extension of the artists’ hypertrophied friendship. They have worked together since 2014, while attending graduate school in Kingston, and often take as a starting point the personal stories that they tell to themselves and to each other. Past work has explored collective drawing practices, particularly drawing as a mnemonic device, and the affective experiences of kinships and coexistence.

Used with permission of Gabriel Cheung, Katharine Vingoe-Cram and Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre.

Ten minutes into our visit with Lise Melhorn-Boe, the floor around our feet is teeming with over a hundred stuffed fabric shapes—they pile up, clinging to one another, trailing into all corners of the room. The shapes are in fact fabric “tubes,” wrestled into letters by Melhorn- Boe via some creative sewing tricks and joined into words. Coming in a variety of patterns, colours and textures, they invite touch (and we oblige). Melhorn-Boe talks excitedly about how the words will hang from up high, vine-like, combining her individual bookworks into an installation; we get excited about walking through this haptic forest of squishy letters.

The playfulness and “cuteness” of the works are perhaps most conspicuous—and put to greatest use—in the darkest, most dismal stories here, recounting experiences about bodily setbacks or interpersonal dysfunctions with humour. Putting the books away at the end of our conversation, Melhorn-Boe is careful with the works, without being precious about them—the way she handles stories in this exhibition feels similar.

NO & NO: The title of your show is RE Books and these works were made to read as books, in that the words come out of covers, with titles, instead of standing alone. We were curious about what a book is to you?

Lise Melhorn-Boe: I have been making books for forty years and I call myself a book artist. And so, I think of what I make as books. These are definitely books to me—they have covers, they open, they have text inside. It just happens to be quite fat, bouncy text that spills out of the covers.

N&N: Annette Messager’s Sewn Words were mentioned earlier as a source of inspiration for your RE Books, and formally, the works look very similar. At the same time, the use of repetition here leads us to read your books differently. There are formal repetitions, with all the words beginning in RE—for example, reawaken, remember, readjust—but also invisible, manual repetitions that constitute the making of these works, where you’re sewing a lot of Rs and a bunch of Es. We were thinking about how this repetition relates to memory as persistent work.

LM-B: Certainly doing something over and over again is a way of remembering it. I will definitely remember for the rest of my life making these letters. There’s a reason why people use mantra for meditation. I do Kundalini Yoga and we do a lot of chanting and it is very calming and soothing. Similarly, I have found it very enjoyable and relaxing to sit and make these letters. A lot of people who do hand work as artists feel that. It certainly is meditative. Because of my son’s brain injury, memory has played a large role in my household’s life in the past few years. And so I’ve been thinking a lot about memory and these pieces have kind of coalesced a lot of the vague thinking that I’ve been doing over the past few years.

N&N: You’ve brought up aspects of your son’s story, which are intertwined with your own and make their way into your works. You’ve also mentioned how your sister was not only the inspiration for one of the books, but also a collaborator, in that she chose one of the RE words. The books, from the clues on the covers to the words inside, seem charged with these personal stories, not just about yourself but also variously about people close to you, people you’ve encountered. What are your thoughts on telling these stories publicly and navigating these public disclosures?

LM-B: In my earlier work, where I was looking at women’s life experiences, including with their bodies, I would create questionnaires and circulate them, starting with friends. But then they would send them to people that I didn’t even know! I’d ask for stories, with the understanding that I was going to use their stories, and people would get excited about the questionnaires because they liked being part of it! Not all of the work directly pertained to me but all the subjects that I was exploring were things that I was interested in. What I found was that so many people could relate to the stories because, although people’s stories may be specific, chances are someone else has experienced the same thing. Didn’t somebody say they are no new stories?

N&N: We were also interested in thinking about the ways in which you tell stories in these books. They seem to very much be aware of and engaged with this question of legibility.

LM-B: Because of the nature of the material, the words sometimes spin and sag, and so it will be a little bit of a challenge for the reader to read the words. But there are only three words for each book, so I think that it’s not going to be too arduous a task.

N&N: Yes. And we love how the works are sometimes generous, divulging their stories in these playful and colourful ways; but sometimes they are also shy, spinning and sagging, as you say, away from readers’ sights, withholding their stories and only revealing three words.

LM-B: It’s true that if you can’t read the words you are not going to get the complete story. But in this case, I won’t say I don’t care, but I’m so excited about the shapes of the letters and the sculptural effect and as I mentioned the spaces in between. I think if someone just comes and looks and says “wow that’s cool,” that’s probably fine too; and if they want to delve in and actually look at the title of the book and then try to read the words they are going to get more out of it. I have really worked with colour as well—you can get a sense of whether this is a happy book or a sad book just seeing what colours I’ve used. So even if you couldn’t read each word, you might get something from it.

Harvesting Environmental Justice

Heather Saunders

Written in 2014, for the exhibition, It's Fine...It's Fine...Everthing's Just Fine, at the Window Gallery, Kingston School of Art, Kingston Ontario. Heather Saunders is an artist and the author of artistintransit.blogspot.com. She is adjunct faculty in the Department of Fine and Peforming Arts at Nipissing University, where she also works as a librarian..

Used with permission of Heather Saunders.

“Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap. I have aimed to tell the truth as I saw it. If this book shall have borne ever so feeble a hand in garnering a harvest of justice, it has served its purpose.” ~ Jacob Riis

In 2008, I took the bus from Ottawa to Kingston to visit Lise Melhorn-Boe. I arrived feeling agitated because it was only days after the grisly death of Tim McLean aboard the very bus line with which I was travelling—one province west, granted, but far too close for comfort. Unbelievably, southern US Baptists interpreted it as pay-back for the Canadian tolerance of abortion, homosexuality, and adultery.

While we visited outdoors on a beautiful summer day, the artist described the health symptoms caused by mold in her house in North Bay, which had forced her to sleep in her front porch in the dead of winter. She relayed these details while cheerily stitching photographs of houses on her street into pages that would form the book, Homeless (2008). Then we played a game with her son, who had recently come out of a coma following a car accident, because it was good for cognitive recovery. (This too would become the subject of a bookwork, Diffuse Axonal Injury: April 14, 2008 [2014]). By the time I left, my nerves were settled, and I dare say I felt slightly optimistic about life in general

That’s her gift: making lemonade out of lemons—pesticide-laden lemons flown across international borders or organic lemons packaged in frustratingly non-recyclable materials. She uses her own and others’ stories to challenge the viewer to consider that maybe it’s not all completely a lost cause, that maybe society won’t collectively win the Darwin Awards and bring about its own obsolescence through intolerance and carelessness. The fact that only some of her stories have silver linings reinforces that it could go either way. One that stands out is Gypsy Moth (2007), about a woman who was incapacitated after accidentally being aerially sprayed with pesticide intended for gypsy moths; amazingly after two and a half grueling years, after deciding that she would indeed recover, she did just that.

Melhorn-Boe has witnessed firsthand the benefits of shifting perspective. Reminiscent of Hannah Wilke before Wilke was diagnosed with cancer and making uncharacteristically expressionistic self-portraits in watercolour, Melhorn-Boe turned to the same medium and envisioned herself healing from the mold-related symptoms in the book, Mind Over Matter (2010). The book’s first image is a Nancy Spero-esque grey, zombie-like frontal portrait with a double head and bruises against a background that resembles shattered glass. In the final image, the artist assumes a more dynamic pose, in profile and dancing to what must be groovy 1960’s music based on the bright biomorphic forms in the background and her equally vibrant attire.

As a society, we are in desperate need of such a perspectival shift. Every person I’ve told about Melhorn-Boe using empty potato chip bags as garbage bags has responded with, “She must eat a lot of chips!” No, I explain: she’s hardly a glutton; her diet is very healthy. She just diligently minimizes the amount of garbage she produces. They can’t seem to wrap their heads around it. Her compost bin contains things most people have probably never even heard of composting, and her recycling bin contains not just her own refuse, but bottles and cans she has found on the street while cycling. Naysayers can check out her books, Garbage (2007) and More Garbage (2010), which incorporate all of the garbage, with the exception of organic waste, that she generated during a given period of time (plus some gloves and mittens found in the streets during the creation of the latter work). In these works, to borrow a term from South African Zanele Muholi who documents positive and negative subject matter to fight social injustice, Melhorn-Boe functions as a visual activist.

In viewing her environmental bookworks collectively, there is a disturbing sense of humanity being at risk from day one, evident in Endangered Species (2011), which features pink and blue onesies; Toxic Kids (2009), a paperdoll book; and Home Sweet Home (2009), a quilted dollhouse. Melhorn-Boe’s cautionary tales are often delivered with a wry sense of humour, rhyming couplets, and formats ranging from tunnel books to star carrousel books. These appealing features have a similar resonance as the stereotypical woman saying in a suspiciously enthusiastic tone, “I’m fine.” In an interview in 2012, Melhorn-Boe told me that she felt that in spite of her lighthearted approach, audiences had an attitude of, “I don’t want to know this” in response to this particular body of work. However, just as placating the woman who says, “I’m fine” will lead to no good, these are tales that need to be told—not unlike the bookwork that might be seen as the precedent for It’s Fine… It’s Fine… Everything’s Just Fine. That book is Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives, a photo-documentary exposé of the deplorable living conditions in turn-of-the-century tenement buildings.

The convergence of art and book for social reform dates back at least to 1890 with Riis, but the modern concept of the artist’s book really developed in the 1960s, coincidentally (in the context of Melhorn-Boe) in lockstep with the environmental movement. Her early works focused on feminism; for example, the house motif was used to convey abuse in Little House/Happy Home, and in fact, uses the same Little House quilt pattern as Homeless. Then her work shifted to ecofeminism with works like Toxic Face Book and Body Map (2009) and the effect of the environment on women’s health became her focus during an artist residency at Queen’s University in 2006. The lines blur between art imitating life and life imitating art, providing fertile ground for the harvest.

Return to top

Telling and Retelling: Some Remarks on the Bookworks of Lise Melhorn-Boe

Gil McElroy

Written in 2006 for the exhibition, Once Upon a Time. Gil McElroy is a poet, artist, critic, and independent curator. He currently lives in Colborne, Ontario with his wife Heather.

© Gil McElroy. Used with permission.

Erratum: The book entitled Germangoodgirls was created in collaboration with Clarissa Lewis. We constructed the book over several months with parcels and emails flying back and forth between our studios in North Bay and Toronto. Long distance collaboration was an unusual way of working for both of us, one that we thoroughly enjoyed.

In many ways, it could be argued that the artist’s book is the quintessential

20th-century artform. ~ Johanna Drucker

Once upon a time there was black and white television. I’m old enough to have grown up with it, and remember the excitement in our Tacoma, Washington neighbourhood when my father purchased a colour television in time to watch the first Superbowl. It had pride of place in the rarely used living room, while its b&w ancestor was relegated to the family room.

That was in the mid-1960s. Colour television was relatively new on the market, but by no means a new technology. Its “untimely” early development had, in fact, posed a significant threat to the market for black and white sets, so the leading corporations of the time sat on the new kid for awhile so as to be able to recoup their investment in its older sibling first.

I relate this story by way of talking about the book and, more specifically, about artist Lise Melhorn-Boe’s bookworks. Television (and I apologize to radio) was arguably the "quintessential" technological development of the twentieth century, and if American book artist Johanna Drucker is right in her assertion made at the start of her The Century of Artists’ Books (New York: Granary Books, 1995), then I think there is a parallel that makes it worth the mention.

These days, television is an evolving technology, but the book as we’ve known it since the days of Gutenberg is a technology under threat of something akin to extinction. Handheld electronic readers into which a text can be downloaded have been a reality for some time, though the obvious technological advantages of the traditional book form—portability, ease of access, no power requirements, etc.—have kept its electronic offspring at bay. So far, anyway. The proverbial writing is on the wall; the inevitability of an entirely new technology finally superseding what is actually a very old technology (that indeed predates Gutenberg) is becoming more and more apparent. As far as technologies go, the book as we’ve known it has had a good run.

But the artist’s book is another issue entirely. By and large outside of the commercial impetus that has driven book technology, emancipated of its commodity status, the artist’s book is free to explore other aesthetic, social, political and cultural terrain. It is so with Melhorn-Boe’s work.

That’s not to argue that the critical conventions of the book are dispensed with in Melhorn-Boe’s work; she is, in large part, observant of them—like, for example, the codex structure comprising individual pages bound together at a central spine, or the book as a linear narrative device. With her Once Upon a Time, Melhorn-Boe turns these conventions in upon themselves. It’s a cloth work comprised of square stitched panels joined together to form a 12-panel long linear structure when entirely unfolded. On each cloth square is a word or sequence of words that, collectively read through the sequence of panels, form a coherent sentence. Or actually, sentences, for every second panel section is itself a multiple thing, a compendium of seven panels joined together at the top with metal rings and which affords the opportunity for the construction (depending on which panels are flipped into place) of variant sentences and thus possible meanings. All, however, must start with a non-variable: the familiar narrative device, “Once upon a time…” It’s all about storytelling.

At the core of Melhorn-Boe’s work is storytelling, and so its narrative conventions are of enormous aesthetic use as devices of social response and reaction. In her books Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast, and Many-Fur, Melhorn-Boe creates feminist retellings of classic fairy tales using advertising imagery and snippets of text culled from popular fashion magazines set within the narrative form established by the works’ codex form and heightened via the use of complex pop-up and fold-out structures of the kind often found in children’s literature. As with all of Melhorn-Boe’s work, content and form mutually support one another, ensuring that one does not disappear in favour of the other (unlike a conventional mass-produced novel, where the book form, and even the page itself, is fully intended to disappear behind the story narrative).

Retellings are key to Melhorn-Boe’s work. She doesn’t just rework classic fairy tales, but also relates more contemporary narratives–specifically, stories told her by friends. In Someday (a work in which the codex form is reimagined so that the spine holding pages together is transformed into a hinged cloth box that contains the work’s loose pages—here, paper cut in the shape of doll dresses—within it), Melhorn-Boe retells the story of Marilyn Zimmerman’s feminist reworkings and reconfigurations and of fairy tales for her daughter; tales like “The Four Little Pigs,” in which the fourth pig is the sister who comes to tell her brothers that the wolf has already departed, and they are simply fearing fear itself. And in Library Book, paper artist Wendy Cain’s story of moving from a rural farm into a home in the town of Cornwall near the public library, and her subsequent discovery of the Fairy Books of 19th century writer Andrew Lang is retold by Melhorn-Boe in a hardcover codex with pop-ups.

With Clarissa Lewis’s story, Germangoodgirls, Melhorn-Boe makes a radical formal departure. Lewis’s story, as with others Melhorn-Boe has retold, is about growing up—“growing up as Germangoodgirls,” as the story is told—and concludes:

But if being good means traveling through life with courage

and an open heart, listening to what’s needed in the world

and responding without thought of personal gain, perhaps

we need more fairy-tale heroines.

We don’t follow this story, however, as a linear narrative progression through a codex. Here, the pages of the work are sculptural elements—tori, flat paper “doughnuts” connected together vertically, the work opening by being drawn upwards so as to unfold into a columnar shape. But Lewis’s story isn’t a part of the individual page-elements; rather it’s written on the binding that connects the tori together. Melhorn-Boe literalizes the narrative thread by denying a distinction between the material and the semantic. We must experience them—medium and message—as one and the same. Her point is clear: stories bind us together.

Once upon a time there was a colour television. The first Superbowl wasn’t all it showed; the horrors of the war in Vietnam now entered our home in full living colour. And though my family lived in a neighbourhood of American air force personnel where the conflict had very real, very immediate, and very devastating personal consequences, in the end it was television and what it showed that bound us together. In her bookworks, Lise Melhorn-Boe may have us recall and remember the formative capacities of the story, but most significantly, she shows us the power in its telling.

And its retelling.

Past Lives

Joan Murray

Written in 1998, when Joan Murray was the Director of the Robert McLaughlin Gallery, in Oshawa, for the exhibition, NOW i KNOW HOW TO BE A GOOD GiRL.*

Used with permission of Joan Murray.

*This exhibition title came from Rohja Lawrence, in response to seeing some of this work.

Memoirs of the time before you were born, written by your parents, can be enlightening. These strangers, who knew nothing of you—who lived without you—became your mother and father, but seem very different from the parents you are used to. Circumstance is partly to blame for this: the woman who preferred a solitary existance can find herself married, the man who disliked children can find himself a father. Artists who are women find a special edge to their interest in reading the journals of their mothers, especially those who had mothers who were also artists, because so many women artists of an earlier day were doomed to financial failure.

Lise Melhorn-Boe was born in 1955 in Rouyn-Noranda, a mining town in northwestern Québec. She grew up in a creative household: her mother was an abstract painter, Pauline Gillmore Meilman, who in 1954 married Kurt Melhorn, an electrical contractor, and moved north. Melhorn-Boe, the eldest of three daughters, showed artistic talent at an early age. After courses in architecture at Carleton University, she took printmaking at the University of Guelph, and from 1981 to 1984 studied for her Master of Fine Arts in Fibre at Wayne State University in Detroit. Then, with the support of her mother, who bought her first works and paid her studio rent, she hit the Toronto scene, met and married musician David Boe, and in 1990 moved to North Bay, where she lives today. At the same time, she produced a remarkably affecting body of work based on her feminist insights and a formal inventiveness, often involved with book-making. Her printed material might be in multiples or single works; but always the result reflected her delight in the handling of unpretentious materials. What counted was her touch; she maintained a finely graded technical ability with an oddly elusive sensibility that could veer, in one and the same moment, from the subtle to the boldly evocative. Through her work, she gestured with winsome irony toward the wider culture while confirming her citizenship in the little nation of art. A book, for Melhorn-Boe, could be of the widest possible application: Hairy Legs (1982, edition of 10) featured loose paper pages in the shape of life-size legs and, on the cover, a hand-spun raimie and hair stocking held closed by garters; in Marilyn’s Grandma (1993), she hand-printed (on flannel pages) a story from a friend, and “illustrated” it with hair rollers and pin curlers, hair nets, baby doll pyjamas, nightgowns and pillow embroidery. The stories Melhorn-Boe likes to use are narratives from real life, her own and others’ (often collected through questionnaires) as in the work she entitled Wandering Foot (Migration) (1993) in which she used the wandering foot pattern of traditional quiltmaking, sewn onto the reverse side of cloth maps of Canada. The quirky part comes on the backs of the blocks where, in ink, she wrote the stories of women who had to move because of their husbands’ jobs; the blocks are attached in an erratically unfolding shape, like a well-used or torn road map.

Melhorn-Boe had long known of her mother’s habit of keeping a journal; she often talked about them, saying that she was gathering information for a novel about her husband, but that she did not want to hurt his feelings so she was waiting till after his death to write it. But only after her mother’s death in 1990 did she read the journals to which her mother had confided her true feelings. Melhorn-Boe began to reclaim her own life then, seeing it through her mother’s eyes, in her mother’s own writings. Saddest of all, were her mother’s words about her life, especially about the things she was not doing, but wished that she could—painting and writing poetry and short stories. She was an unhappy housewife, and her personal narrative covered the area of unfulfilled desire. To these imaginings and laments written by her mother, Melhorn-Boe gave an appropriate form—reproductions in sheer nylon of articles of clothing her mother had worn; inside each garment, she hung a panel with a black, rubber-stamped text she had taken from her mother’s account corresponding in date to the period of the dress. On the teenager’s dress (around 1940), for instance, she wrote, “I wanted to go to art school but my father said, ‘Foolishness! You'll never be able to earn your living that way.’”

As with any everyday object taken out of context, these garments, hung in a line, carry a suggestion of human life, not least because they serve as body surrogates. The words shift and waver, gathering shadows, and where the fabric folds, giving a moiré effect, they overlap, playing on top of one another. Through the eight parts of Ghost Costumes: Pauline, Melhorn-Boe records the evidence rather than washing it away, almost as though the words had become a from of progressive memory.

The work of Melhorn-Boe has been interpreted through highly publicized lenses, including that of feminist theoretical analysis. Surely its power stems from its evocation of absense and the losses that accompany memory; it recalls our own mortality, our sadness at the finite nature of our parents’ lives, and the unknown ghosts at whose bidding we live. Ghost Costumes: Pauline and her other bookworks marry the personal and the political, and give meaningful expression to the disenchantments of married life.

Return to top

Harvesting Environmental Justice: The Bookworks of Lise Melhorn-Boe

by Heather Saunders

Telling and Retelling: Some Remarks on the Bookworks of Lise Melhorn-Boe

by Gil McElroy

Past Lives

by Joan Murray

Creative Meaning-making

by Tara Hyland

Home/bodies

by Carolyn Langill

Fairy Tales and Family Fables